Your

Source

for Equine

Fitness Plans

Explore Semi- and Fully-Customizable

Fitness Plans for Your Equine Partner

Find the Right Fitness Plan for Your Equine Partner

Online Courses

I focus on what works and I can’t wait to share that with your horse AND you.

My online courses let you benefit from my decades of training no matter where you’re located in the world.

Each course, includes step-by-step guides to tune up your horse’s overall fitness, postural muscles, and balance. While we focus on the three most important aspects: Improving Horse Fitness, Enhancing Comfort of Movement, and Increasing Overall Athleticism.

Best of all, the course material NEVER expires, you can go at your own pace, and you can always return for a review or refresh.

Ready to begin? Click here to explore my full lineup of online courses.

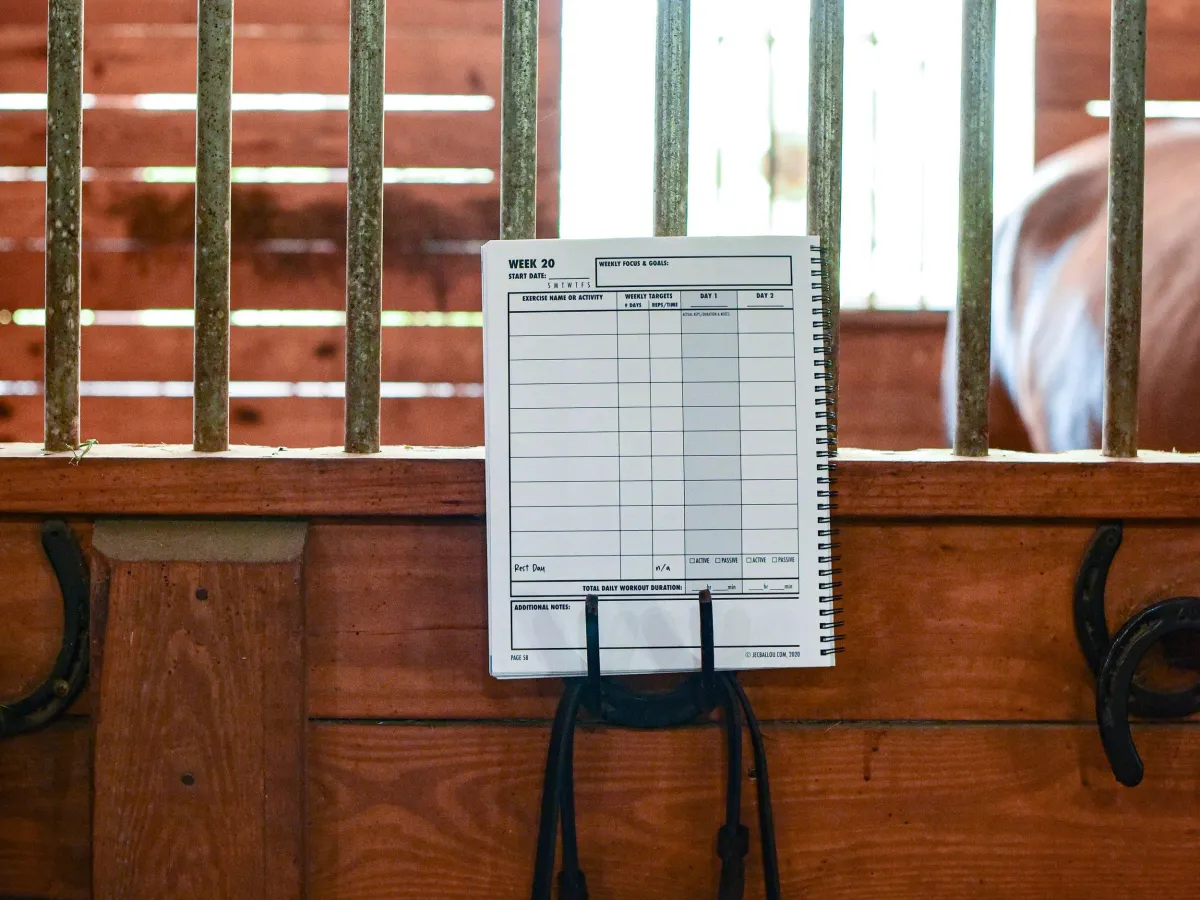

Custom Fitness Plans

Enjoy the results of a training and conditioning plan made specifically for your horse. Have you ever wondered which exercises are best for your horse? Or how to add fitness progressively without over- or under-exerting? Take the guesswork out and receive a day-by-day plan that covers 4 weeks of training prescriptions.

My approach has solved problems for horses struggling with balance and strength, finding correct movement, rehabbing from injury, and performance anxiety/burnout.

I have also designed plans for senior equine athletes and those transitioning from groundwork to riding after prolonged time off.

Ready to for your plan? Click here to get started with your plan.

Clinics & Workshops

Throughout the year, I offer a limited number of in-person clinics and workshops.

My clinics offer a calm, positive environment where you will learn both how to do specific moves but more importantly, you’ll also learn

why to include this in your equine’s fitness plan.

I teach you how to effectively ask your horse to move.

Horses and riders just like you leave clinics fitter, with more comfort in movement, with a greater level of athleticism, and with a game plan for future training to address weak spots or imbalances.

Ready to join me at one of my upcoming clinics? Click here to explore my schedule.

Get to know Jec

I am a horse trainer and top-selling author of multiple books that have become pillars in the equine industry. Combining an expertise in equine exercise physiology and classical dressage, my methods lead riders and their equine partners to measurable progress by relying on simple, straightforward instruction focusing on proper biomechanics and athleticism.

Improve your riding with one of

my top-selling books.

Get free training tips on my blog.

What Type of Exercise Suits Your Horse Best?

This allows muscle fibers and energy systems to be recruited, taxed, and then recover. The body absorbs the exercise stimulus this way as opposed to just tolerating it. There is a big difference between the body adapting to training on a weekly basis versus going through the motions without underlying physiologic changes.

Horse Heart Rates

and Training

While dressage— and other arena sports— places relatively low aerobic demands on horses, emerging studies have shown that occasional exercise at higher heart rates may improve muscle function.

Let’s explore the use of heart rates during arena training, and how riders can use it to improve physiology.

How to Keep You Horse Fit

Without Riding

As the shorter, colder winter months settle in, brief but purposeful groundwork sessions become critical for a horse's physiology. Granted, fitness-based groundwork will not keep a horse at peak performance level, but it will prevent total erosion of neuromuscular and metabolic fitness during times of abbreviated schedules.

What others are saying

—A Happy Student

“I have a senior warmblood and believe me Jec’s conditioning and corrective exercises have helped with stiffness and stumbling issues. No more stumbling. No more Preivcox. The results are amazing. The simple things work.”

— Jackie and Cowgirls Hotrod

“You are helping and inspiring so many horse owners who are applying your methods to benefit their horses.”

— Delaya of Cool CA

“Thank you so much for all the extra effort; you gave much more than was expected and then kept at it till you got results. It was encouraging to watch Mystic change.”

— Cheryl Beller

“It is rare to experience the breadth and depth of what you offered all of us at your clinic today.”

Stay connected.

Sign up to receive news, exclusive offers, and free training tips.